The phase contrast method of diascopic illumination was invented by Frits Zernike, for which he won the 1953 Nobel Prize in Physics. It is a technique that enhances contrast by darkening the background, but, unlike crossed polarizers, doesn't require the subject to be birefringent.

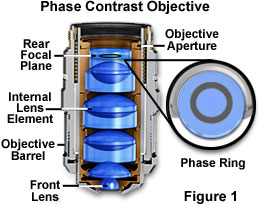

It requires a specialized objective (the following diagram is from Nikon's Microscopy U) as well as a matching annulus in the condenser. Phase annuli in condensers can be translated to match exactly the phase ring in the objective, which is what the two knobs in the photo are for.

The above images show the phase ring, through a Bertand lens, misaligned (left) and properly aligned (right).

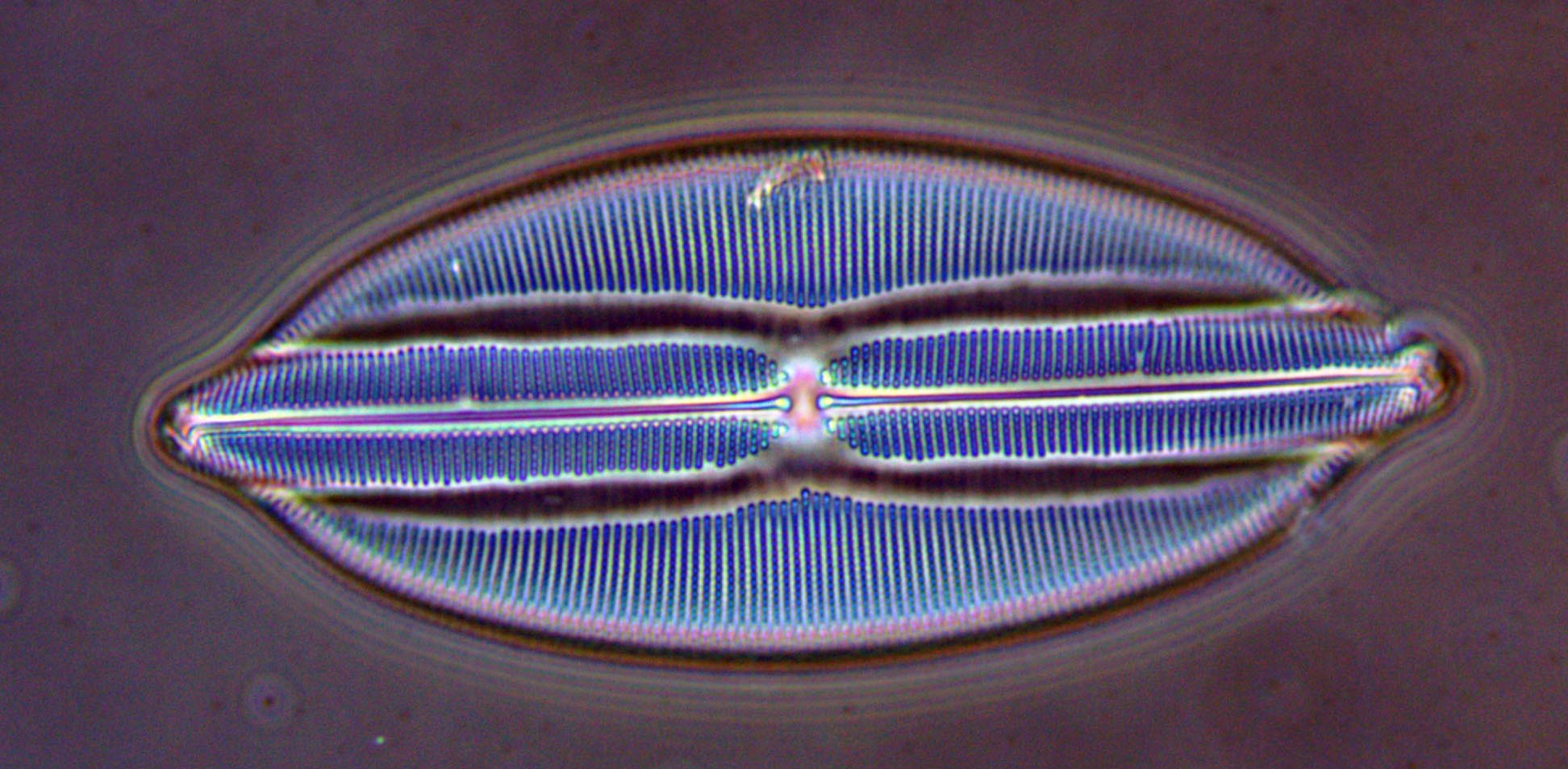

One of the tell-tale features of phase contrast is that objects tend to have artificial "halos", so it is usually fairly obvious when an image was taken with this technique. Below is a comparison of a diatom (prepared by Charles Baker, London) with low NA brightfield on the left and phase contrast on the right. They are both with the same 40x objective, with different condenser settings.

Here is a couple of diatoms from Carolina Biological on a test slide, first at 40x Ph3, and on the right is a comparison of three different 100x Ph4 objectives, dark low, dark low low and dark medium (DL, DLL and DM), which have different optical densities in the phase rings.

With the proper condenser and objective, it can also be a useful technique at high magnification. Below is an image of my live blood cells, which are generally difficult to see, with 100x Ph4. You can see many red blood cells starting to stack up (this is how they coagulate) like pancakes, as well as white blood cells. The halo effect is quite prominant in this image.